More Australian Brinsmeads

Horace Clowes Brinsmead was the son of Edgar William Brinsmead and Annie Bailey. He was born on February 2nd, 1883 in Hampstead, London. He had two elder brothers, Edgar John and Howard, and two sisters, Lydia and Florence. Horace’s mother had north of England roots. Father Edgar was one of the “& Sons” in the John Brinsmead & Sons piano firm. Although blind, he authored a book, The History of the Pianoforte which ran to several editions; a detailed text criticized however for being too pre-occupied with the qualities of the Brinsmead brand.

Horace appears to have been named after his youngest Brinsmead uncle, Horace George Brinsmead.Unlike his older brothers, Horace George was adventurous from an early age and went to sea. He spent most of his life in Australia, looking after the colonial trade for the piano firm as well as pursuing his own interests as a plantation owner in the Cairns area of northern Queensland. There is little doubt that uncle Horace George had a major influence on his nephew’s early development.

Horace Clowes Brinsmead attended school in England at Clifton, Cranleigh and then Repton.

At age 20, Horace Clowes migrated to Australia and settled in North Queensland. His venture there was unsuccessful and he left for Tonga where he is said to have managed a tea plantation. An article later said of this period:

It was not all that he had expected it to be. But it was an outlet for his energies, and he needed that. It sweated all the English out of him. Because of it people think that he is an Australian. It gave him that hard bitten, lean look of his. It gave him one of those faces that you can’t tell the age of, and it was the kind of thing that gives a man an independent mind.

He remained in Tonga until the outbreak of World War 1.

Horace left Tonga for Melbourne, which was closer than returning to England. On December 29th, 1914, he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force as a private and was posted to the 24th Battalion. He was commissioned a second lieutenant while training at Seymour, Victoria. On June 26th, 1915, he embarked for active service.

The balance of his war service is described in the Australian National Biography:

On 29 December 1914 Brinsmead enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force as a private and was posted to the 24th Battalion. He was commissioned second lieutenant while Brinsmead training at Seymour, Victoria, and on 26 June 1915 embarked for active service. When his battalion reached Gallipoli in September Brinsmead, by then lieutenant, was appointed adjutant. He was firm, just and courteous towards other ranks who, because of his slight build, gentle nature and quiet disposition, thought at first that he was 'too refined to make a leader in war'. He proved his ability during the heavy Turkish bombardment of Lone Pine on 29 November. Sent in to command 'B' Company when the front line had been blown to pieces, he quickly reorganized the men and had the trenches rebuilt so that a fresh Turkish attack could be met with confidence. He served at Lone Pine until the evacuation and commanded the last party to leave the sector.

The 24th Battalion reached the Western Front in March 1916. Brinsmead, who was still adjutant, was promoted captain in May, and for gallantry at Pozières on 27 July was awarded the Military Cross. On the same day he was severely wounded in a leg and evacuated to England. Nine months later he was still unfit for active service and after attending a senior-officers' course at Clare College, Cambridge, transferred to the administrative staff at Australian Flying Corps headquarters, London. From April 1917 until early 1919 he was a senior staff officer in the A.F.C. training wing. He was promoted major in January 1918 and temporary lieutenant-colonel a year later.

The decision to award Horace the Military Cross for bravery in the field was announced in London with the New Years Honours for January 1st, 1917. His O.B.E. (Military) was awarded on June 3rd, 1919, cited for service with the 24th Battalion, AIF in Palestine.

From April to November 1919 Horace Clowes Brinsmead was attached to the Foreign Office for special duty with the military section of the British delegation to the Paris Peace Conference. His recruitment was at the instance of John Hartman Morgan K.C. who wrote, in the Times of London, a few months after Brinsmead’s death:

From April to November 1919 Horace Clowes Brinsmead was attached to the Foreign Office for special duty with the military section of the British delegation to the Paris Peace Conference. His recruitment was at the instance of John Hartman Morgan K.C. who wrote, in the Times of London, a few months after Brinsmead’s death:

He was “attached” to the British Military Delegation at Paris, but not as an original member of it, the Delegation being entirely confined to English officers. He joined it as my Assistant on my application to General Macdonough for his services, in April, 1919, and soon made himself at home among the little group of fellow Australians already gathered there as members of the "British Empire Delegation,” among them Robert Garran and J. G. Latham, now Attorney General of the Commonwealth, and the four of us enjoyed many happy hours together, at Fontainebleau and elsewhere, entertained by Brinsmead's caustic wit and lively flow of reminiscence.

He was given the O.B.E. in June. In November 1919, he was sent to Germany with the Disarmament Control Board. Brinsmead described this as “…his worst job. Being in a country of enemies was dismal. So was the weather.”

After the war, Brinsmead had the task of telling one of his best mate’s fiancé, Ivy McDonald, that her intended had died in the War. Later, the two became close and married, on December 8th, 1920 at the Presbyterian Ladies College in East Melbourne.

Ivy Ernestine McDonald was born in September 1893, the daughter of Charles McDonald and Mary Ann Tregear. Her father Charles was a politician belonging to the Australian Labour Party. Known as “Fighting Charlie”, he was first elected to the Queensland house, but after Federation stood for Labour in the Division of Kennedy, Queensland, co-incidentally the area where Brinsmead, Australia is located. He twice served as speaker of the Australian House of Representatives, and kept his Kennedy seat until his death in 1925.

The couple lived at Widmore, Queens Road, Melbourne. They later lived at 31 Ranfurlie Street, East Malvern, Victoria, Australia. By 1931 they lived at 58 Broadway, Kooyoung, Camberwell North,

They had three children; Margery, born in 1921, Pamela born in 1923, and Clive, born in 1925.

Mrs. Brinsmead was active in Melbourne society. She was the Secretary of the Queenslanders’ Association that held an annual Derby Day dinner and dance in Melbourne and a number of prominent social functions. Mrs. Brinsmead was a very active golfer and the Honorary Secretary of the Kew Golf Club.

At the same time, Lieutenant Colonel Brinsmead had many official functions to perform due to his position. He actively promoted Flying Clubs. He opened many aerodromes, a particularly significant one being the new Western Junction facility near Launceston, opened in the presence of a crowd of 20,000 people in March of 1931 which gave residents of Tasmania a direct air link to the mainland.

The Australian parliament passed the new Air Navigation Act on December 2nd, 1920, and it became law on June of 1921. Lieutenant Colonel Horace Brinsmead was appointed its first Director General with difficult tasks to manage. While a number of well-trained pilots returned to Australia after the war, Australia’s flyers prior to that had something of a cowboy reputation. Some sectors of the industry were bitterly opposed to the new regulations. Brinsmead’s task was to introduce new airworthiness checks for planes, qualifications for those who serviced them, and new medical inspections and licensing requirements for pilots.

For more information on Horace Clowes Brinsmead's role in Australian aviation, read the book Flying Matilda by Norman Ellison, or check the Airways Museum's website.

One of Colonel Brinsmead’s responsibilities as Director of Civil Aviation was to plan the civil aviation routes and suitable aerodromes for Australia’s growing aviation industry. This industry was vital the new country; with its huge landmass, its rural outback, and its several major cities separated by many hundreds of miles.

On May 13, 1922, under the headline “Unknown Country Crossed in 9,000-mile Flight” the Times of London reported that Colonel Brinsmead had just completed an aerial tour of Australia in a “Bristol Tourer”. They suggested it ranked “…as one of the finest flying achievements which has yet been recorded.”

In July 1924 it was announced that Colonel Brinsmead intended to fly right around Australia. He left Point Cook, near Melbourne in a biplane piloted by the Superintendent of Flying Operation, Captain Cook. They flew for 85 hours, over 22 days, circling Australia without a hitch. The purpose was to inspect potential aerial routes.

The picture on the right was taken at Wyndham Six Mile, Western Australia, on

August 17th, 1924.

In July 1924 it was announced that Colonel Brinsmead intended to fly right around Australia. He left Point Cook, near Melbourne in a biplane piloted by the Superintendent of Flying Operation, Captain Cook. They flew for 85 hours, over 22 days, circling Australia without a hitch. The purpose was to inspect potential aerial routes.

The picture on the right was taken at Wyndham Six Mile, Western Australia, on

August 17th, 1924.

In late 1925, Colonel Brinsmead used the same plane for a flight from Melbourne to Normanton on Australia’s Northern coast, flying 1,600 miles in just two days. The first leg of the flight covered the early route of the Queensland and Northern Territories Aerial Services more familiar today as QUANTAS, the Australian national airline.

Horace Clowes made at least one visit to the United States of America, leaving Sydney on November 17th, 1928 to San Francisco aboard the SS Ventura. While he was away, Mrs. Brinsmead, her mother Mrs. MacDonald and her three children went to stay at Ulverstone, in Tasmania for three months.

In late 1931, Colonel Brinsmead was involved in two crashes in a row. By then, the airmail service between Australia and London, England was a major undertaking and Colonel Brinsmead was instrumental in its development, along with one of the route’s pilots, the famous Australian Aviator Air Commodore Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, famous, among other things, for winning the Australia to England Air Race in 1930.

On November 26th, 1931 Colonel Brinsmead was travelling to England in the Southern Sun, a plane carrying the Christmas mail. The plane took of from Alor Star, the capital of what was then Kedah, in the Malayan States. The plane crashed right after take off. The crew was unhurt, but Colonel Brinsmead, the only passenger, was slightly hurt. With the sange froid that only the British can muster, it was duly noted that the mail was intact.

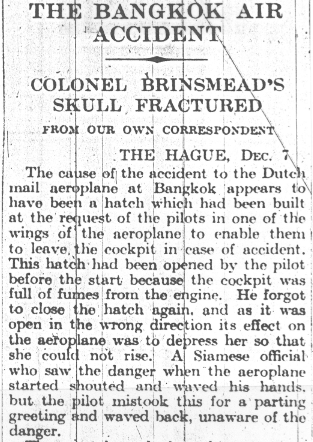

On December 6th, 1931, Colonel Brinsmead was set to travel on in a Dutch mail plane. It took of from Donmuang Airport in Bancock with a heavy cargo of 500lbs of mail, four crew and three passengers, including Colonel Brinsmead. An escape door in the side of the plane, built for emergencies, had been left open after it was used to clear the cockpit of fumes. This created a drag that prevented the necessary lift and resulted in the crash. Three of the crew and two of the other passengers were killed. Colonel Brinsmead was very seriously injured. His skull was fractured and ribs were broken. Initially, a paralysis developed which gradually improved. The story was reported the next day in newspapers in England and Australia. The Times of London report from December 8th, 1931 is shown to the right. Once again, it was duly noted that the mails were saved with only two bags suffering water damage.

Brinsmead was initially kept in Bangkok and then taken home to Australia via Singapore.

In late February, 1932, Colonel Brinsmead arrived in Brisbane and his wife flew up from Melbourne to meet him. He stayed with her uncle and aunt, Mr. and Mrs. A. P. W. Tregear, of Bowen Hills.

After his return to Australia he then stayed with a friend in Coogee, Sydney, where he underwent treatment with a nurse specially trained in rehabilitation. This followed a critical operation transferring nerves to replace those damaged and training them to do the work of the old ones. He had to have help with his voice to restore normal speech, and needed special glasses for close vision. He was reported, despite all these challenges, to continue to take a keen interest in everyday affairs.

Horace Clowes Brinsmead died on March 11th, 1934 at the Austin Hospital, Heidelberg, and was cremated the next day and interred in the Fawkner Cemetery, Sydney Road, Fawkner, Victoria.

The obituary in the Times of London noted, in part:

Although not himself a pilot, Colonel Brinsmead was keenly interested in aviation, and his air mindedness and enthusiasm were revealed in many ways. From the time he took over the control of the Civil Aviation Department he made a practice of travelling by air and a DH 60 was reserved almost exclusively for his use. He toured Australia and carried out all his inspections by air; he was the type of man who looked ahead and, convinced that there was a great future for aviation in Australia, tried by example and propaganda to get people to think along the same lines as himself. His aerial tour of 9,000 miles, much of it through practically unknown country, which he completed in May, 1922, ranked as one of the finest flying achievements which had till then been recorded. A genial companion and a good sportsman, he was liked by every one.

Horace’s widow Ivy died in December 1939, in Hawthorne, Victoria.

Since his death, Horace Clowes Brinsmead has had a street in the Australian Capital Territory named after him; Brinsmead Street in Pearce, not to be confused with Hesba Brinsmead Street in Franklin, named after Reg Brinsmead’s wife, the famous children’s and environmental author.

Since his death, Horace Clowes Brinsmead has had a street in the Australian Capital Territory named after him; Brinsmead Street in Pearce, not to be confused with Hesba Brinsmead Street in Franklin, named after Reg Brinsmead’s wife, the famous children’s and environmental author.

In 1951, Qantas also named one of their new fleet of L749 Constellations “The Horace Brinsmead” pictured to the right. It was used to fly the Queen to Australia in 1954.

Margery Brinsmead married Sidney Hunt. They had two daughters, Robyn and Jennifer.

Pamela Brinsmead worked as a nurse, both in Australia, and at sea. She is also an accomplished yachtsman having served on an all women crew in the famous Sydney to Hobart yacht race.

Clive McDonald Brinsmead married Catherine Elspeth McColl. They had three children, John Bernard, Katrina and Andrew Clive. He worked as a construction engineer and was involved in building the zinc smelter at Boolaroo, Newcastle between 1959-1960.