The Brinsmead Lawsuits

Throughout the 1890s and into the first decade of the 1900s, the newspapers regularly reported on lawsuits, charges and countercharges involving the use of the Brinsmead name.

How it all began

John Brinsmead and Sons built up a very large and prosperous business. It relied, for its ongoing success, upon its good name, the advertising and promotion used to sustain that good name and the quality of its products.

John Brinsmead and Sons, in the 1870s, had taken steps to buy out the business of Henry Brinsmead, John's older brother, thinking that, by buying up and securing retirement from the trade, of the only other Brinsmead piano manufacturer at the time, their use of the name would be exclusive and secure. And so it was, rather to the detriment of Henry's family, until about 1893.

John Brinsmead and Sons employed many hundreds of workers. A significant number of these men (and they were almost all men) came from North Devon and some were members of the extended Brinsmead family. In particular, the firm employed Thomas Edward Brinsmead, the son of John's younger brother George. George appears to have been the family black sheep; he was a sailor who declared bankruptcy, left his wife and children in Bideford and (at least we know now) ended up in Liverpool married to another woman. More on George elsewhere. Thomas Edward in turn had a large family including two boys who worked for the John Brinsmead and Sons firm; Edward George Stanley Brinsmead and Sidney Walter Brinsmead.

One day, John's son, who managed the factory either caught, or heard about, Thomas Edward, his two boys, and another man named Willcox making pianos "on the side". They said they were made in their own time and for their own use; John Brinsmead and his sons thought otherwise, and all four men were summarily dismissed. They felt aggrieved but they had no significant remedy in those days.

Setting up their own firm

Thomas Edward Brinsmead and his sons, rather than seek work with another firm, decided to set up their own firm. They rented some premises and began making pianos putting them up for sale under the name of Thomas Brinsmead and Sons. This action met with legal action commenced by John Brinsmead and Sons, the allegation being that by using a similar firm name (albeit their own name, by birth) they were guilty of passing off their product as what John Brinsmead and Sons considered "the genuine article". The law on such matters in those days was less developed than it is today, and the case eventually made legal history on that count alone. The first major suit thus involved an application for an injunction to restrain Thomas Edward Brinsmead and his sons from producing pianos under the Brinsmead name.

The following document includes copies of the formal court documents filed over this claim (the pleadings).

The first page of The Investor advertisement.

See the link below for a full and larger copy

The first page of The Investor advertisement.

See the link below for a full and larger copy

The Decision to Incorporate

To appreciate the next step in the story, it is important to realize that Company Law was at the time in its infancy. There were few laws in place to protect investors and there were clever and unscrupulous men about ready to exploit those with money to invest. More details on those involved will follow; for now it is sufficient to introduce them only as a group of promoters affiliated with a publication called "The Investor" and operating a companies called Consolidated Contracts Corporation and Consolidated Exploration Corporation.

Business at the fledgling Thomas Brinsmead and Sons firm was not booming. The promoters persuaded Thomas that he should incorporate the firm and, in exchange for some ready cash and a share in the soon to be incorporated company, allow them to offer shares to the public. Once this was agreed, the promoters set about preparing advertisements and a prospectus. They dolled up the premises to make them look prosperous and took photographs to be used to prepare the engravings for the documentation. They prepared circulars and generally put it about that this was a good investment in which members of the public should subscribe.

What the promoters were less than careful about was making it clear to the public that the firm they were being invited to invest in was not the well known and long established John Brinsmead and Sons firm, but the newly formed Thomas Brinsmead and Sons Ltd.

Winding Up Proceedings

John Brinsmead and Sons were quick to respond to this public offering. In addition to renewed legal steps to restrict the use of the Brinsmead name, John had his lawyer, Walter Maskell, arrange for a Mr. Richardson to become a shareholder in the new company.

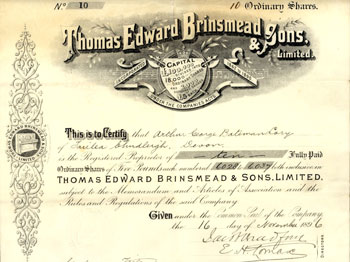

An original share certificate in T. E. Brinsmead and Sons Ltd. from the editor's collection

An original share certificate in T. E. Brinsmead and Sons Ltd. from the editor's collectionArmed with that legal status, Richardson,, as a "straw man" on behalf of the John Brinsmead and Sons' firm interests, commenced yet more court proceedings, this time to have a receiver appointed to prevent the proceeds of the share sales being siphoned off and for an order winding up the new company on the basis that it was insolvent. These proceedings, which became complex and protracted, are explained in more detail below. Eventually, a winding up order was made on December 3rd, 1896. That order was then appealed to the English Court of Appeal.

Once a receiver and winding up order were in place, yet more proceedings were brought to set aside some of the improvident contracts the promoters had arranged in order for them to syphon off the money from the Thomas Edwards and Sons Ltd. firm. These proceedings too unfolded over time.

Criminal Proceedings

All this did not bode well for Thomas Brinsmead and his sons. The matter was heard before the magistrates over six days. By late 1896, a criminal indictment had been brought against Thomas Edward Brinsmead, his two sons and the promoters for conspiracy to defraud, false pretences and several other charges. It was initially to be heard in the Central Criminal Court (the Old Bailey) but motions were made to have it heard in the Court of Queen's Bench because of the complex company law issues involved.

Eventually, the matter came on for trial in the Queen's Bench Division in January and early February, 1898. By then, one of the promoters, Lomax, had disappeared. The papers contained day by day accounts of the evidence and arguments. The defendants were convicted and sentenced to jail.

Lingering Issues

Despite all the fireworks over the Thomas Brinsmead and Sons stock fraud, the underlying issue of when and to what extent a person could use their own name in making and selling pianos was never quite resolved. It continued to have repercussions on both sides of the family. Edgar George Stanley Brinsmead continued, in a small way, to produce and sell pianos using his own name "Stanley Brinsmead". Once again, the John Brinsmead and Sons (by then Limited) firm once again took court action to try to stop his use of the name.

Within John Brinsmead's own family, these lawsuits had also brought about some strain. John, although fit and healthy, was getting older, as, by them were his children. In 1900, the firm had decided itself to incorporate, which made firm governance somewhat more difficult. For a time, youngest son Horace George came back to England to take over as managing partner, but disputes arose and he left, subsequently setting up his own Brinsmead piano business drawing on his contacts in Australia. John's son Thomas also withdrew from the firm. He too experienced opposition when he began trading pianos using the name.

This has been but a quick summary of a very complex and heated decade or more of litigation. Details will be added as time permits, drawn from the newspaper accounts at the time and our review of the original court files in the civil, criminal and bankruptcy proceedings.

- The advertisement in The Investor for the shares in Company

- An original share certificate in the new T H Brinsmead company

- The petition and schedule of investors from the winding up law suit.

- The Court decision in the main action to wind up the Thomas Brinsmead and Sons Limited Company.